There’s a pretty famous scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho that involves a shower, a knife, and some screeching violins. It’s said that the scene was so frightening to audiences at the time, that people actually became afraid to take showers. Whether that’s true or not, it’s understandable that an audience from 1960, who hadn’t seen a lot graphic violence in films yet, would be disturbed by such a brutal slaying. In 2013 Marion Crane’s murder looks rather tame. Modern audiences are desensitized. The trailer to Evil Dead (2013) is more gory than all of Psycho. Yet having watched Psycho recently, I still found myself feeling unsettled after Marion’s death, not because of how she was killed, but because of how the camera behaved immediately following her murder.

Normally cameras don’t “behave” at all. In most movies you’re rarely aware of the camera work. Maybe you notice if there are too many quick cuts, if the camera sweeps into the distance to give you a bird’s eye view, if it spins or twirls or uses continuous close ups. But in general you’re not thinking about what the camera is doing, so long as it’s following the action of the story. In Psycho¸ we’re introduced to Marion Crane as the film opens, and we follow her all the way to the Bates Motel. As far as we know she’s the focus of the entire story. And then she’s killed, leaving the audience in a “what happens next?” moment. If she’s dead, who will we follow? What will the camera show us? We don’t get an answer right away either. The camera first focuses on Marion’s dead, open right eye. Then it slowly pulls away. It switches focus onto the running shower for a moment before panning across the bathroom and then leaving the bathroom to enter the main bedroom. It looks at the newspaper on the nightstand, and then trains itself on the Bates house where it spies Norman shouting at his mother about the “blood.” And right then we know who we’re going to follow next.

It’s as if the camera is a creature that exists to watch action unfold. When it first finds Marion in a compromising situation, it’s thinking Jackpot! It follows her, and her actions keep proving riveting. But then she dies. Presumably it could focus on her eye for eternity, or until it runs out of film, but that isn’t interesting. So it begins to wander. It’s searching. The shower? No. The newspaper? No. That guy Marion was speaking to earlier who is screaming at his mother? Jackpot! If you’re wondering what this has to do with Chan-wook Park’s Stoker (and you really should be, what with me three paragraphs into an analysis of the cinematography in Psycho), all this is to say that the camera work in Stoker is a major contributor to the unsettling feeling that permeates the entire film.

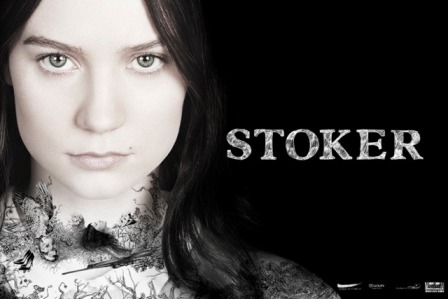

The movie opens with India Stoker (played by Mia Wasikowska) on her 18th birthday moments before she learns that her father was killed in a car accident. After the funeral, her father’s brother, Charlie (played by Matthew Goode), comes to live with India and her mother, Evelyn (played by Nicole Kidman). He’s not so much estranged from the family as he is disavowed. No one ever told India she even had an Uncle Charlie. And from the moment we meet him we see that maybe there was good reason for it. There’s sinisterness in his everything he does. He moves so deliberately. He has intense, soul-searching eyes, eyes that are consistently drawn to India. He’s not so much physically threatening as he is unnerving. India feels it even though her mother feels something quite opposite. Yet the longer he’s there, the more India is drawn to him despite herself. This leads to some very interesting and disturbing results, though maybe not so surprising given the tone the movie presents from the beginning.

The movie opens with India Stoker (played by Mia Wasikowska) on her 18th birthday moments before she learns that her father was killed in a car accident. After the funeral, her father’s brother, Charlie (played by Matthew Goode), comes to live with India and her mother, Evelyn (played by Nicole Kidman). He’s not so much estranged from the family as he is disavowed. No one ever told India she even had an Uncle Charlie. And from the moment we meet him we see that maybe there was good reason for it. There’s sinisterness in his everything he does. He moves so deliberately. He has intense, soul-searching eyes, eyes that are consistently drawn to India. He’s not so much physically threatening as he is unnerving. India feels it even though her mother feels something quite opposite. Yet the longer he’s there, the more India is drawn to him despite herself. This leads to some very interesting and disturbing results, though maybe not so surprising given the tone the movie presents from the beginning.

The entire film is nerve-wracking and tense. Part of the reason is the camera work. There are several scenes where characters are simply conversing: either they’re at the dinner table or they’re standing, but they’re more or less motionless. During these conversations the camera will deliberately swing around to focus on the speaker. If someone else speaks, it’ll pan or turn to face him or her. Usually in these kinds of scenes we’re used to seeing cuts to different cameras that capture different perspectives. So when a camera actually moves, it draws attention to itself. We become aware that the camera is choosing what it wants to look at, and it adds tension of the scene. If the camera is choosing what it looks it, then it has some sort of will and desire. If so what does it think about what it sees? Is it trying to show me more than I’m seeing?

This kind of movement also reminds us that we’re at the mercy of the camera. It’s going to show us what it wants to. This is true of all movies of course, but usually we’re not aware that we’re prisoners to the camera’s will, which is not to say that we’re consciously aware of it as we watch Stoker, yet I think we do experience, if only subconsciously, a feeling of helplessness as we follow the whims of the camera at the dinner table. And Uncle Charlie is not the kind of guy you want to feel helpless around.

The way the film uses sound also contributes to the uncomfortable feeling the movie wants to create. Certain sounds are amplified beyond their normal decibel levels. At one point India is rolling a hard-boiled egg back and forth across a table top, and we can hear the flecks of the shell cracking off as she applies pressure with her hand. There’s another scene with India sharpening a pencil that has a drying red liquid on it (which may or may not be blood), and we can hear the sliver of wood being shorn as she twists the pencil. It’s loud, and it sounds wet and sloshing, and for some reason it’s unsettling. It’s explained early in the film that India has enhanced sense of hearing. So amplifying the ambient sounds puts us in India’s shoes, but it also makes things feel more tense in the same way that a tight shot on a person hiding in a closet in a horror movie will make us feel tense because we’re blind to the dangers outside the closet. When we’re listening to India and Charlie play the piano together we’re focused so much on the beautiful sounds they’re creating that we’re not giving our full attention to Charlie in a moment that is pregnant with potential action and danger.

It’s in the atmosphere that Stoker really excels. I can’t say the same for its story (written by Wentworth Miller or as you may know him, Michael Scofield from the Fox TV show Prison Break) and its characters. The actors were great, without question, but I didn’t quite understand everyone’s motivations. It was never really clear to me why India and her mother were at such odds, except that maybe they both were competitors for the father’s attention and then later Charlie’s attention. India has a transformation in the movie that, while it doesn’t come out of nowhere, I didn’t see coming, and I’m on the fence about whether I even buy the transformation or not. Maybe it’s just not earned enough. So while I liked everything about how the story was told, I just didn’t connect with it. Still, it was a pleasure to experience and one I completely recommend.

My Rating

Stoker

Director: Chan-wook Park (Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, Oldboy, Lady Vengeance)

Writer: Wentworth Miller, Erin Cressida Wilson (Secretary)

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags:

The Hobbit: Battle of Five Armies (1/13/15)

The Hobbit: Battle of Five Armies (1/13/15)